Table of Contents

I. Preamble

- The Goals of HIV Care

- Why HIV Clinical Care Guidelines for Ontario?

- How Were the Guidelines Developed?

- The HIV Care Cascade and Continuum of Care

- How are the Guidelines Organized?

- Identifying Markers of Clinical Care – Indicators/Evaluation

II. List of All Recommendations in Guidelines

1. Organization and Delivery of HIV Care

2. Initial Linkage to Care and Assessment After Diagnosis

3. Near Term Follow-up After Initial Asssessment

4. Antiretroviral Therapy Across the Continuum of Care

6. Recommendations for Other Populations

- Inside/Out – Incarceration and Release

- Adolescents and Transition

- Pregnant Women

- Transgender Men and Women

7. Well Being, Quality of Life, End of Life

III. Appendices

I. Preamble

The Goals of HIV Care

Ontario HIV/AIDS Strategy to 2026

Vision

By 2026, new HIV infections will be rare in Ontario and people with HIV will lead long healthy lives, free from stigma and discrimination.

Mission

To reduce the harm caused by HIV for individuals and communities and its impact on the health care system by ensuring timely access to an integrated system of compassionate, effective, evidence-based sexual health and HIV prevention, care and support services.

Goals

- Improve the health and well-being of populations most affected by HIV

- Promote sexual health and prevent new HIV, STI and hepatitis C infections

- Diagnose HIV infections early and engage people in timely care

- Improve health, longevity and quality of life for people living with HIV

- Ensure the quality, consistency and effectiveness of all provincially funded HIV programs and services

The goals of clinical care for people living with HIV are to:

- Provide effective ongoing (life-long) treatment for HIV

- Manage other health issues, co-infections and co-morbidities

- Address any social determinants that could affect the person’s health or ability to stay engaged in care

- Improve overall quality of life.

Why HIV Clinical Care Guidelines for Ontario?

High quality, consistent and accessible care is essential for people living with HIV. With effective treatment and care, people with HIV can live a near-normal lifespan. Life expectancy for a 20 year-old individual in the U.S. or Canada on combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) may approach that of the general population.1 Fully effective suppression of plasma HIV-1 RNA or viral load (VL) through the use of cART can profoundly reduce mortality and morbidity.2

Some Ontarians with HIV who are on treatment are doing well, but disparities persist. Life expectancy and mortality for individuals accessing cART in Canada differ by sex, injection drug use (IDU) history, Indigenous ancestry, CD4 count before initiating ART, and by time of ART initiation. In general, the life expectancy of people with HIV in Canada remains lower than that of the general population.3

The use of comprehensive HIV care guidelines can improve health outcomes.4, 5 Focusing Our Efforts – Changing the Course of the HIV Prevention, Engagement and Care Cascade in Ontario, the HIV/AIDS Strategy to 2026 released in February 2017, recommended the following to improve the health, longevity and quality of life for all people with HIV:

“… the Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (MOHLTC) will work with HIV providers to:

- Establish standards of care for people with HIV, including the use of care pathways that help people navigate the system and stay engaged in care

- Strengthen HIV care delivery by building needed capacity and better care coordination.”

The guidelines are intended to:

- Optimize clinical management of HIV infection

- Empower patients to be engaged in their care, act as their own best advocates and make informed decisions.

The guidelines set out evidence-based practices to help engage people with HIV in care in a timely way, retain them in care over time, address challenges that may cause them to fall out of care (e.g. access issues, personal, social and economic circumstances, substance use, incarceration,6 depression, distrust of the medical system, trauma, treatment “fatigue,” feeling “well” so not feeling an urgent need to access care 7, 8), assess them for relevant health issues across the life course, and monitor all aspects of their health, including access and adherence to cART.9, 10

These guidelines may be used in any Ontario health care setting where people with HIV access care, including specialty HIV clinics, primary care practices, shared care models, through emergency departments, in long-term care settings and in correctional institutions. They may also be a valuable reference tool for providers new to HIV care, and those working in an evolving provincial healthcare delivery system.11, 12

Notes:

- These guidelines do not replace professional judgment or decision-making between a patient and provider, alter the privacy of the patient/provider relationship or provide guidance on prescribing any specific cART drug regimen or drugs to manage co-infections or comorbid conditions.

- These guidelines do not include recommendations for caring for infants or children with HIV. Clinicians caring for children with HIV can receive advice and assistance from the two large specialized pediatric centres in Ontario that provide this care. These centres can also provide guidance on early and prompt treatment or pre-emptive combination therapy for high-risk infants. Infants exposed to HIV in utero should receive PEP and be tested for HIV at birth.

How Were the Guidelines Developed?

At the request of the AIDS Bureau, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care, the Ontario HIV Treatment Network (OHTN) brought together an interdisciplinary working group, including infectious disease and primary care physicians, people living with HIV, nurses, clinic coordinators, pharmacists, and registered dieticians and social workers (see Appendix B). The group was supported by staff from the AIDS Bureau and the OHTN.

The OHTN HIV Clinical Guidelines Working Group reviewed research evidence and recommendations from guidelines developed in other jurisdictions13–21 and followed recognized principles for evaluating and implementing guidelines produced by others22, 23 – including discussing differences among the guidelines.24 The group did not conduct independent assessments of the recommendations produced elsewhere.

Members identified gaps or recommendations where more evidence was required and examined the available peer-reviewed and grey literature. Where questions or disagreements occurred, members worked with the OHTN’s knowledge synthesis team to conduct additional research and analysis, or considered best clinical judgement.

Guidelines Reviewed from other Jurisdictions

| BHIVA 2011 | British HIV Association guidelines for the routine investigation and monitoring of adult HIV-1-infected individuals 2011 |

| BHIVA 2015 | British HIV Association guidelines for the treatment of HIV-1-positive adults with antiretroviral therapy 2015 |

| BHIVA SR | British HIV Association, BASHH and FSRH guidelines for the management of the sexual and reproductive health of people living with HIV infection 2008 |

| BHIVA Women | British HIV Association guidelines for the management of HIV infection in pregnant women 2012 |

| PPG | Canadian HIV Pregnancy Planning Guidelines |

| WHO | Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection |

| IAPAC | Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with hiv: evidence-based recommendations from an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care Panel |

| DHHS | Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-Infected adults and adolescents |

| DHHS Ped | Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in pediatric HIV infection |

| IAPAC CC | IAPAC guidelines for optimizing the HIV care continuum for adults and adolescents |

| BC | Primary care guidelines for the management of HIV/AIDS in British Columbia |

| IDSA | Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with HIV: 2013 update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America |

| DHHS Women | Recommendations for use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant HIV-1-Infected women for maternal health and interventions to reduce perinatal HIV transmission in the United States |

The HIV Care Cascade and Continuum of Care

HIV care and treatment are now routinely measured against the continuum or cascade of care,25 which focuses on improving the number of people diagnosed who are linked to care, retained in care over time, placed on antiretroviral therapy and who achieve and maintain a suppressed – and ideally – an undetectable viral load.

Maintaining an undetectable VL26 is good for individual health because it reduces damage to the immune system, reduces chronic inflammation and inhibits disease progression. It is also good for population health because someone with an undetectable VL is significantly less likely to transmit the virus to others.27 The goal for health systems is to maximize the proportion of people living with HIV who achieve VL suppression as well as other markers of a functioning immune system.28

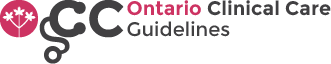

UNAIDS has established the 90-90-90 targets for the HIV care cascade:

- 90% of people infected with HIV will be diagnosed

- 90% of those who are diagnosed will be on treatment

- 90% of those who are on treatment will be virally suppressed.

In the HIV/AIDS strategy to 2026, Ontario’s HIV sector has made a commitment to achieve the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets for the care cascade. Fig. 1 illustrates Ontario’s best estimate of its HIV care cascade in 2015.

Figure 1: Estimated Proportion of People with HIV in Ontario at Each Stage of the Care Cascade, 2015

Notes to chart: Percentage of people diagnosed with HIV is based on 2014 modeled preliminary estimates provided by the Public Health Agency of Canada. Percentage on treatment and virally suppressed are based on 2015 data from the Ontario Public Health Laboratory.

Keeping VL Measures in Perspective

While an undetectable VL is a desirable endpoint, it is not enough on its own to ensure the health, well-being and quality of life for all people with HIV. Some people with HIV will not achieve or maintain full VL suppression or will need more intense care to address their specific needs.29 A suppressed viral load is also not enough to assess the health of “immunological nonresponders” (INRs) – people who may achieve and sustain an undetectable VL but whose CD4 counts remain low: a sign that their immune function is still significantly impaired.30, 31 This group – which may account for 10-20% of people with HIV in care in the province — has comparatively poorer health outcomes and requires careful clinical monitoring.

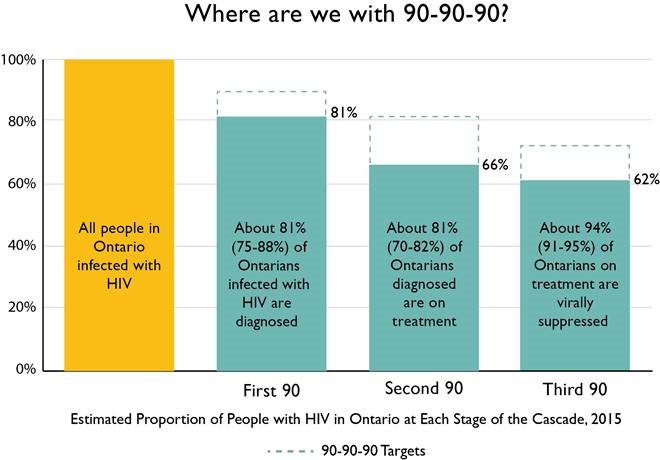

The commonly used HIV care cascade is focused solely on ART treatment and suppressing viral load. It does not include management of comorbidities or promotion of optimal health. To acknowledge that gap, Ontario has developed a broader cascade (Figure 3) that includes primary care and care for other health conditions, co-infections or co-morbidities. It illustrates how people receiving lifelong HIV treatment may experience gaps in care, and it highlights the importance of efforts to retain them, reduce loss to follow-up and, when applicable, re-engage people in care in a timely way.10

Figure 3: The Engagement and Care Cascade for People Living with HIV

Clinical care is not the only factor in improving health and well-being. Biological, individual, social and structural factors also play a role. To encourage comprehensive person-centred care, these guidelines highlight the need for active links to other supports, such as housing, psychosocial care and harm reduction services. As a recent Canadian commentary stated: “a concerning picture emerges when we examine those in care who have multiple psychosocial syndemic risks. Across all populations, those who experience a syndemic of co-occurring mental health and addiction issues are significantly more likely to fall out of care, less likely to adhere to treatment and less likely to achieve/maintain an undetectable viral load.” 32

How are the Guidelines Organized?

The guidelines begin with recommendations on the organization and delivery of HIV care.

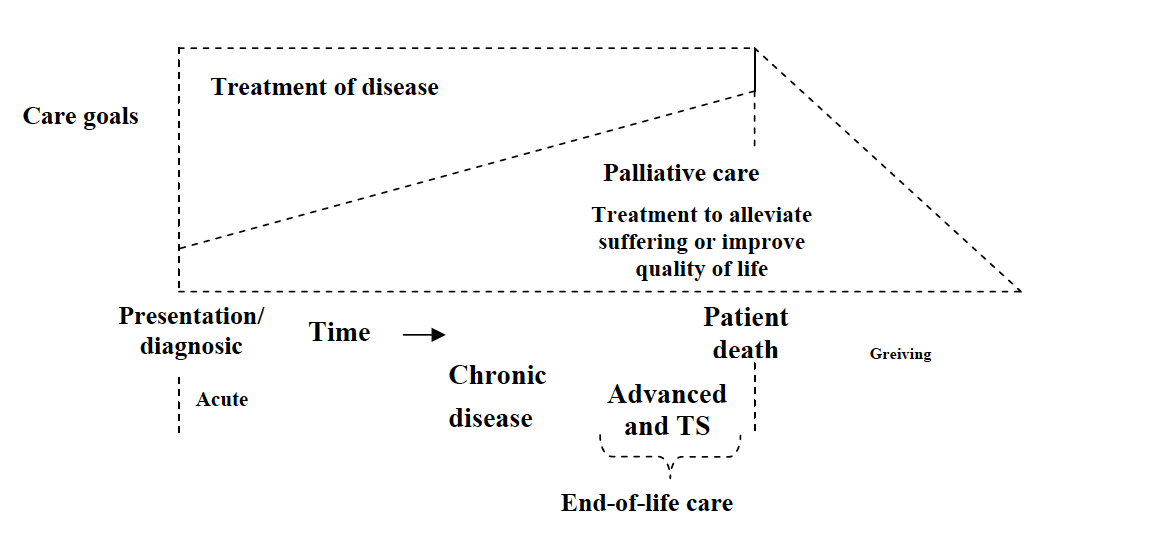

The guidelines use a “patient journey” approach, beginning with diagnosis and then following the patient from the initial assessment or first visit(s), to initiation of treatment and ongoing care and support – as illustrated in Fig. 3. They focus on the person’s history and life course, and include strategies to reduce/manage co-morbidities and other health issues. The guidelines also include recommendations on ongoing access to cART across the continuum of care

For people living with HIV, the guidelines clarify what they should expect from their providers. For health care providers, the guidelines set out expected assessments, tests and investigations as well as their recommended frequency. They include practical checklists that can be used in real-world health settings to ensure people with HIV receive comprehensive assessments.

Identifying Markers of Clinical Care – Indicators/Evaluation

The working group will produce separate recommendations on criteria and metrics to measure:

- Individual clinic/practice implementation of the guidelines

- The impact of the guidelines on patient empowerment, satisfaction and health outcomes

- The impact of the guidelines in: increasing the number of people with HIV who are retained in care and achieve health goals (including but not limited to suppressed VL); and in helping Ontario achieve the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets.

II. List of All Recommendations in Guidelines

1. Organization and Delivery of HIV Care

These guidelines encourage integrated models of care that involve an interdisciplinary team-based approach. Team members may be located within the health care setting or be part of a broader network of services in the community.

The care of people with HIV may be shared between specialists and primary care providers. When primary care providers refer patients to specialists and when specialists refer patients to primary care providers, both must be clear on their roles (i.e. the aspects of the person’s care that each provider is responsible for) to ensure the person receives comprehensive care.

General Recommendations

1.1 Comprehensive HIV care should be provided by an interdisciplinary team of HIV-knowledgeable professionals who can offer integrated care and wellness as well as appropriate and timely linkage or referral to other health and social services. Providers should be aware of the network of services in their area, have easy access to these services, and cultivate relationships to ensure effective referrals and linkages.

Patients have better outcomes when they have access to integrated multidisciplinary care teams.33–36 The team could include physicians, nurses, pharmacists and case managers as well as professionals skilled in psychosocial support, sexual and reproductive health, substance use counselling, mental health expertise (including psychiatric care and psychotherapy), social services navigation, nutrition, rehabilitation services and co-morbidity experts. Depending on the specific clinic/practice and its staffing, team members may be able to provide more than one domain of care. Teams who do not have access to all the recommended professionals/skills should work with available resources to ensure that people with HIV achieve the best possible health outcomes.

1.2 Physicians providing HIV care should be highly knowledgeable and experienced in the management of HIV infection. Physicians who do not have this experience should consult with an HIV-experienced physician.14, 15, 19 This process may include the use of telemedicine,37 mentorship and/or shared care.

People living with HIV have better health outcomes when they are cared for by experienced physicians who have a critical mass of HIV-positive patients in their practice and are able to maintain their HIV care competencies.38–44 HIV expertise may be based on managing a minimum number of patients with HIV (e.g. 25 according to some medical associations, 50 according to another recent study, 20 in another review) and/or ongoing certification.11, 33, 45, 46 This recommendation is especially relevant in Ontario where a substantial number of people with HIV receive their care exclusively from primary care physicians.11Providers who do not have that expertise – particularly those working in settings where people with HIV occasionally access care (e.g. emergency rooms) – have a responsibility to consult with those who do.

1.3 People with HIV and their interdisciplinary clinical care team may benefit from the services offered by community-based AIDS service organizations (ASOs).47 Many ASOs offer practical support services as well as peer-based programs to empower people with HIV to be actively involved in their care and make informed decisions about their treatment.48

Ontario has a network of 33 ASOs that are specifically funded to provide prevention, education and support services for people with or at risk of HIV. ASO services can augment those available through public assistance programs. For patients with complex social needs, the interdisciplinary clinical team can work with ASOs to provide HIV case management, including assistance with engaging/relinking and retaining patients in care, adherence support, appointment reminders, transportation to appointments, counselling related to stigma and disclosure, and support to apply for food programs, housing, access to drug coverage and income supplements.49 Providers can refer patients to an ASO and ASOs can help connect people with HIV with HIV-knowledgeable providers. A small number of Ontario ASOs are co-located with HIV clinics to facilitate case management.47

1.4 Providers should create a trusting/therapeutic relationship with patients.

A trusting/therapeutic patient/provider relationship enhances engagement and retention in care and adherence to cART.50, 51

Specific behaviors and attitudes that facilitate a therapeutic relationship and effective engagement and retention include connecting through being present and attentive, validating through non-judgment and respect, and partnering through collaboration and shared decision-making. Behaviors that are barriers to engagement include patronizing, condescending and demeaning attitudes and communications styles, and being autocratic around decision-making.52 Patients with more avoidant and disorganized coping styles are at greater risk of dropping out of care unless a strong health care relationship and therapeutic alliance is fostered, ideally from the first visit on.53

To elicit patient input about how to enhance therapeutic relationships and quality of care, some Ontario HIV clinics have established an independent patient advisory committee or include patients on quality committees.

1.5 The practice setting should deliver sensitive, culturally competent care to all patients and create an atmosphere of respect, cultural safety, compassion and acceptance.19

Most people living with HIV experience stigma in their daily lives – some traumatically so. To create the trusting patient/provider relationship essential to engage and retain people in care, clinics/practices should provide a stigma-free environment. Providers should reassure patients about the respectful non-judgmental attention they can expect to receive and what the practice will do to safeguard their privacy.14,15, 19, 54 Efforts to reduce stigma and reassure patients may be particularly important in practices with few HIV patients or in locations/communities where individuals may face strong stigma and are fearful about disclosing their HIV status. Especially when partnering with Indigenous peoples to build a therapeutic relationship, providers should respect and validate the patient’s way of knowing and being as part of culturally safe care.55

Providers should be comfortable having candid discussions with patients about sexual activities and patterns of sexual satisfaction. Providers should understand that sexual health involves safe and pleasurable experiences as well as preventing disease.

Providers should also be able to elicit sensitive, frank information regarding patients’ substance use, mental health, sexual abuse and other experiences that may affect their willingness to engage in care. They should respect patients’ need for gender affirmation and understand the consequences of intergenerational trauma and histories of discrimination. The populations most affected by HIV in Ontario are heterogeneous and expect their providers to be knowledgeable about the differences.56–60 (See also Promising Practices for how to use pre-appointment screening and patient surveys to solicit candid information.)

2. Initial Linkage to Care and Assessment after Diagnosis

General Recommendations

The patient’s first contact and early encounters with the clinical team (i.e. initial linkage to care and assessment) set the stage for sustained care. In these guidelines, linkage to care is defined as a confirmed care visit, with intake by a nurse, nurse practitioner or physician. Simply referring a patient for an appointment is not considered linkage to care.

2.1 Every effort should be made to link people to care and complete the initial assessment as soon as possible after diagnosis (i.e. when the person receives the first positive test result from a public health laboratory). Providers should be actively engaged with testing services, clinics and public health institutions in their community that facilitate linkage to care.19

Connection to care soon after HIV diagnosis is associated with improved survival.61, 62 Completing the patient’s initial assessment and establishing the trusting relationship needed for ongoing care will likely take more than one visit. All the visits required to complete the patient’s initial assessment should be scheduled as quickly and efficiently as possible, taking into account the emotional reactions many patients may have when first coming to terms with an HIV diagnosis and the fact that both patients and providers may find it challenging to complete the initial assessment within a short period of time. (See checklist of the tests, exams and evaluations that are part of a comprehensive initial assessment and at other key stages of care.)

2.2 Ontario HIV testing sites should provide people who test positive with post-test counselling and practical information to facilitate linkage to care. Providers should collaborate with testing sites to develop and communicate this information.

Every person in Ontario who tests positive for HIV should receive practical, easy-to-read information that explains the importance of connecting to care and accessing HIV treatment and how to access care. Testing sites should have strong working relationships with HIV care providers to help ensure effective referrals and linkages (preferably warm hand offs) to care.

One of the biggest challenges in linking newly diagnosed people to care is finding a physician/clinic that is taking new patients. To overcome this barrier, providers may keep testing sites apprised of their ability to take on new patients or be available for referrals. To ensure that the initial referral results in a true linkage to care (i.e. confirmed visit and complete assessment), providers may adopt protocols such as updating patient contact information at each visit, scheduling appointments to make them convenient for the patient and sending reminders for the first visit(s).63, 64 Post test counselling also facilitates linkage to care.65

2.3 Newly diagnosed patients should have appropriate access to case management services provided by registered social workers and/or ASOs to improve linkage to care.61, 66

Strength-based case management services can increase the proportion of people with HIV who are successfully linked to care. To help patients connect to care, providers may consider referring them to ASOs for counselling, assistance with transportation and peer outreach – although the evidence on the impact of these interventions is not strong. U.S. research on linkage to HIV care has identified an effective ASO-based intervention – Anti-Retroviral Treatment and Access to Services (ARTAS) – that could be adapted for the Ontario context.67

2.4 Within 2 weeks of receiving a positive HIV test result, newly diagnosed people should be seen by either an experienced HIV physician or other health care provider who will order the initial laboratory workup.15, 20 When test providers suspect a person has been diagnosed in the very early stages infection, they are strongly encouraged to arrange a physician appointment within 1 to 2 days.

Because of the benefits of early cART for people with HIV, every effort should be made to ensure that anyone who is newly diagnosed sees a physician within 2 weeks. An immediate response (i.e. within 1-2 days) is critically important for people with very early infection to prevent damage to their immune system and preserve/strengthen immune function.

If providers are experiencing delays seeing patients (i.e. longer than 2 weeks after diagnosis), they may consider working with local testing sites to improve the linkage and referral processes in their area. When physicians who have less experience in HIV care decide to refer newly diagnosed patients to a more experienced HIV physician, they should provide the patient’s records to the new practice as promptly as possible and no longer than 2 weeks after requesting the referral.

2.5 Evidence of HIV infection based on antibody testing or other confirmatory serologic test should be documented in the patient’s medical record. When practical, providers should ascertain whether the infection is recent and the time of exposure.

When a patient transfers into a practice, the physician should have either written confirmation of their HIV infection or repeat the HIV test.13–17, 19 [IDSA- strong/moderate; BHIVA 2011- IIA, IIB and III; BC- AIII] When indicated, tests to determine primary or acute infection can include nucleic acid amplification testing in the absence of positive antibody detection (or detectable HIV-1 RNA or p24 antigen in serum or plasma in the setting of a negative or indeterminate HIV-1 antibody test result.) A presumptive diagnosis of acute HIV-1 infection can be made on the basis of a negative or indeterminate HIV antibody test result and a positive HIV-1 RNA test result. When a low-positive quantitative HIV-1 RNA result is obtained, the HIV-1 RNA test should be repeated using a different specimen from the same patient.13

2.6 The initial assessment should include:

- A comprehensive past and present medical history, physical exam, medication/psychosocial/family history, review of systems and evaluation of sexual and reproductive health and substance use.14–17, 19

- Confirmatory serology, genotyping and testing for immune markers such as CD4 and VL

- Screening for co-morbidities and other STIs

- Other labs to help manage ART regimens and other risks

- A social needs assessment

- Individual and partner counselling.

The focus of the initial assessment is to collect baseline data, gauge the patient’s reactions to a new diagnosis, start educating the patient about care and initiate treatment to stabilize the HIV infection. Initial data collection assists in selecting an appropriate cART regimen and identifying any need for referrals to other services.

During the initial assessment visits, patients should not be overwhelmed with complex health instructions or immediate plans to address non-acute or lifestyle issues such as smoking cessation or chronic bone health. Information about these issues should be recorded on the patient’s chart and addressed at an appropriate time.

Providers should give first priority to critical factors that affect the initial choice of cART regimen, such as patient access and adherence to medication, acute significant risks, primary social contexts and co-infections including: drug/opioid use, other STIs, threats to personal safety, housing (including both homelessness and unstable housing), food security, and drug and health care insurance coverage.

Newly diagnosed patients may need support to cope with the stress of learning about their HIV infection. This support can be provided by many providers, including nurses, peers, ASOs and social workers. Providers may consider assessing patients who have great difficulty adjusting to the diagnosis for new or existing depression.

2.7 Providers should use the comprehensive medical history and exams, review of systems and evaluation of sexual and reproductive health and substance use to establish baseline values, help manage HIV over the short and long term, and identify other health issues, risks and comorbidities.14–17, 19 When prescribing initial treatment for patients who use substances, providers should know the drugs or substances the patients use so they can identify possible drug interactions and assess the effect of substance use patterns on adherence.68

Along with diagnostic data, comprehensive histories, exams and reviews provide baseline information that may influence decisions about which drug regimens to prescribe based on risk and toxicity factors. They may help determine the intensity of monitoring and management of comorbidities the person requires, and assess both the cause of related conditions and preferred interventions.

Addictions and substance use (which often occur syndemically with mental health issues) are a barrier to optimal health outcomes.32 During the initial assessment – and periodically throughout ongoing care – providers should assess patients’ substance use to avoid drug interactions or adherence issues.

Note: When a primary care provider refers a patient to an HIV specialist, the primary care provider may gather most of this baseline data.

See the following recommended sample histories, screens and exams:

- Medical/family history –- from IDSA and BC

- Physical exam – from IDSA/ HRSA

- Medication/vaccination history- from IDSA

- Initial depression and mental health screens with validated short and ultra-short questionnaires (i.e. as few as two questions) that may indicate whether the patient would benefit from a referral for a full mental health assessment. Ultra-short screens may use as few as 2 questions.69, 70

- Review of Systems – from IDSA and BC

- Substance use (i.e. tobacco, alcohol, and drugs – including illicit use of prescription drugs) – from IDSA

- Sexual/reproductive health – from Public Health Agency of Canada and BHIVA, British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (BASHH) Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FRSH) guidelines and UK tables for taking sexual history71–73

2.8 All patients diagnosed with HIV should receive: a CD4 test, a repeated quantitative HIV RNA test (viral load) and viral genotypic resistance testing (using the first available VL sample). Screening for sensitivity indicated by HLA-B*5701 is also recommended.13

Increasing evidence supports testing to determine CD8 counts and the CD4/CD8 ratio at initial testing as a predictor of risk for non-AIDS related adverse events — although testing for CD8 counts is not routinely recommended.13, 74 Patients identified in the very early stages of infection (i.e. especially within the first days, weeks and up to 6 months) should be tested and evaluated for laboratory values as promptly as possible and guided into follow-up care without delay. Providers should discuss with patients the purpose of all tests (e.g. to guide cART therapy) and emphasize early-on mutual decision-making as part of active treatment.

2.9 All patients should receive baseline screening for a variety of other infectious agents, including other sexually transmitted illnesses to assess need for counselling, immunization, monitoring or treatment, and to inform HIV management.13–16, 19 Patients should be screened for the following pathogens:73

- Tuberculosis — using tuberculin skin testing or interferon-gamma release assay. A chest x-ray is recommended for those with increased TB risk to determine active infection for treatment.

- Hepatitis A, B, and C – including Hepatitis A total antibodies testing (or IgG), Hepatitis B surface antigen, surface antibody and antibody to total core antigen (HBV DNA testing if positive) and Hepatitis C antibody test and confirmation RNA testing for those who test positive. Note: In Ontario, testing algorithms may be affected by Public Health Laboratory75 ordering requirements. For patients who are severely immunosuppressed, it is not unreasonable to consider screening using both a screening Hepatitis C antibody test and a PCR test as, on rare occasions, the Hepatitis C antibody test may be negative while the PCR test is positive.

- Syphilis – using a treponemal test with confirmatory testing by RPR, TPPA and FTA-ABS.76, 77

- Gonorrhea/chlamydia – using culture and NAAT testing (urine for males, urine or cervical swab for females). Extragenital testing (rectal, pharyngeal swabs) should be performed in persons with HIV who engage in oral or anal sex.77, 78

- Toxoplasma gondii — using Anti-Toxoplasma IgG testing and counseling to avoid new infections

- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) — Anti-CMV IgG.

- Cervical or anal pap smear, depending on geographic availability

- Varicella zoster — using Varicella IgG for those without history of chickenpox or shingles.

- Measles/rubella — if no documentation of prior measles or vaccination.

2.10 Comprehensive biochemistry and other testing (e.g. liver and renal function, dyslipidemia, CBC, organ system injury, blood pressure, diabetes risk) is recommended to support management of ART toxicities and to evaluate chronic disease, cardiovascular risks, frailty and neurocognitive risks.17

2.11 Patients should receive a social needs assessment and be referred to services that can assess and assist with: applying for disability, health insurance and drug coverage; housing, employment (including episodic employment) and food security; and social support and spiritual or personal coping strategies.19

Social services can also address other barriers to accessing care, such as immigration status, literacy and language, proximity to care and location. Housing (including services to address homelessness and unstable or insecure housing) and health insurance and drug coverage are first stage services urgently needed by people newly diagnosed with HIV.79

Social and economic factors and other determinants are associated with clinical outcomes. For example, improving housing stability has been shown to facilitate adherence to treatment for people living with HIV and has other beneficial effects on overall health and well -being.80 Recent findings from the OHTN Cohort Study (OCS) show that people with HIV who are adversely affected by social determinants of health have significantly worse health outcomes even if they are engaged and retained in care. Robust coordination of social and economic assessments are essential to address the interactions of HIV infection with aspects of daily living.81 The social factors that affect health are even more significant for migratory populations, patients transferring between health care settings and people who move in and out of the prison system; they exacerbate the risk of falling out of or avoiding care.

2.12 All patients should be assessed for income/poverty issues, using the clinical tool developed by the Centre for Effective Practice and endorsed by the Ontario College of Family Physicians.

Poverty increases the prevalence and mortality of many diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer, depression and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. It accounts for 24% of person years of life lost in Canada. Income inequality is associated with the premature death of 40,000 Canadians per year.82 Poverty disproportionately affects racialized Canadians, Indigenous peoples, people with disabilities, the elderly, women and children.

Poverty is a risk factor that warrants intervention. Poverty is not always apparent: in Ontario 20% of families live in poverty.83 The poverty assessment tool developed by the Centre for Effective Practice in collaboration with the Ontario College of Family Physicians and the Nurse Practitioners Association of Ontario84 recommends that: everyone be screened for poverty (i.e. do you ever have difficulty making ends meet at the end of the month?”); the care team consider testing anyone who screens positive for poverty for diabetes and take poverty into account in determining how aggressive to be in ordering investigations into possible health problems (e.g. cardiovascular disease, cancer, mental illness and stress); and the care team intervene by educating patients and connecting them to programs that can help mitigate poverty (e.g. Canada Benefits, filling out their tax returns, legal resources).85

2.13 All patients, regardless of sex, gender, sexual orientation or age, should be assessed for any risk of intimate partner violence, trauma, abuse or other serious personal safety concerns. The HIV care team should have established referral protocols for patients experiencing violence.19, 86

Patients require time and trusted relationships with their providers to feel comfortable responding to questions about abuse. During the initial assessment visits, a single empathetically delivered question may begin a discussion that continues later. As trust develops, patients may disclose more. Clear questions defining types of abuse may help patients understand reportable experiences.87, 88 Several Ontario health units have adopted the Routine Universal Comprehensive Screening Protocol for Women Abuse (RUCS).89The OHTN Cohort Study has developed a gender neutral tool to screen for intimate partner violence.

2.14 Patients and their sexual or drug use partners should receive culturally appropriate counseling related to the risk of HIV transmission.

Patients should be encouraged to notify their sexual and drug use partners and understand both provider-assisted and public health processes for partner notification. They should also be counseled on strategies to reduce the risk of transmitting the virus and given information on/access to prevention methods for themselves and their partners (e.g. testing and awareness, behavioral adaptations, use of condoms, pre-exposure prophylaxis, voluntary male medical circumcision, STD control).64 All efforts to notify and counsel partners should take into account issues such as the patient’s personal safety (i.e. risk of violence), stigma and other complications related to disclosing HIV status.

Every encounter with patients – beginning with the initial assessment – is an opportunity to reinforce strategies to reduce the risk of HIV transmission and to discuss disclosure, provide advice on measures (including harm reduction) that patients can use to protect themselves from exposures to other strains of HIV or other pathogens, and offer referrals to legal experts (e.g. HIV & AIDS Legal Clinic Ontario – HALCO) who can explain criminalization laws, partner notification and other related issues.

Additional Population-Specific Considerations

WOMEN

2.15 Women of child bearing age should be screened for trichomoniasis and rubella, all women with HIV should receive a cervical pap test annually, with follow-up colposcopy or biopsy if abnormal, and women over 50 should have a mammogram.14, 48

Cancer Care Ontario screening guidelines call for cervical pap tests every 3 years for women without HIV, but annual testing for immunocompromised women. Despite these recommendations, women with HIV often receive suboptimal screening. Screening should commence at age of sexual initiation and continue throughout a woman’s lifetime.90, 91

2.16 Asymptomatic gay, bisexual, two-spirit men and other men who have sex with men should be evaluated for lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV) when they: test positive for HCV, HIV or any other STI; have a history of engaging in unprotected anal or oral group sex; and/or have a history of travelling to or residing in an area of Canada or abroad where LGV prevalence is high. Their meningitis vaccine history should also be reviewed.;

AFRICAN, CARIBBEAN AND BLACK POPULATIONS

2.17 Urinalysis and creatinine clearance or eGFR is recommended for African, Caribbean and Black men.17

2.18 A test for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency is recommended for African, Caribbean and Black men and for men from India, SE Asia and the Mediterranean.17

PEOPLE USING RECREATIONAL DRUGS

2.19 When prescribing initial treatment for patients who use substances, providers should know the drugs or substances the patients use so they can identify possible drug interactions and assess the effect of substance use patterns on adherence.68

3. Near Term Follow-up after Initial Assessment

“Near term” follow-up is the series of visits in the first year after diagnosis and assessment (i.e. 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months). During this period, clinics/practices implement and assess the person’s HIV care plan and conduct any other diagnostics that may contribute to the patient’s overall care, health and wellbeing.

General Recommendations

INITIATION OF ANTIRETROVIRAL THERAPY

3.1 Patients who are willing and able should initiate combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) as soon as possible after diagnosis.

Early treatment with and ongoing adherence to cART improves individual health and reduces the risk of HIV transmission. Recent findings from the START Study92 and the TEMPRANO trial93 show that people infected with HIV have a considerably lower risk of developing AIDS or other serious illnesses if they start taking antiretroviral drugs sooner: that is, when their CD4 T-cell count is higher rather than waiting until the CD4 cell count drops to lower levels.28, 92, 93

Note: Medical care is founded on principles of patient autonomy and respect for personal dignity. Patient empowerment and shared decision-making may contribute to improved adherence with cART.94 Because people with HIV may have significant trepidation about starting cART, the decision should be made by the patient without coercion. To support the person’s decision-making, providers should provide the best available scientific evidence on the risks and benefits of cART. Clinicians should also take time to answer any questions and address patients’ concerns, and to explore any structural or personal barriers to cART.

3.2 Patients with very early stage (acute) HIV infection should be counselled about the benefits of starting cART as soon as possible (i.e. before the acute infection becomes chronic).

Initiation of cART during very early stages of infection may reduce the size of latent reservoirs of HIV and promote physiological conditions that make it more likely the person will benefit from strategies to cure infection or achieve remission.95–98 These strategies are currently in the early stages of basic, preclinical and preliminary clinical study. Other benefits of treatment in the very early stages of HIV infection include: preserving immune function, reducing morbidity and reducing the risk of onward transmission.48, 99

3.3 Physicians should review initial laboratory values and select an appropriate cART regimen, taking into account the patient’s other comorbid conditions (if any), use of other drugs and access issues.

3.4 Once the patient’s HIV infection is stable, the HIV care team should establish a regular schedule to monitor the patient’s physical and mental health, medication, family history, sexual history and substance use.16

3.5 Clinics/practices should establish a laboratory monitoring schedule for each patient based on the patient’s decision to initiate or delay cART, any concerns about virologic failure, drug toxicity and immunological response, and the need to manage ongoing care.

Some individual clinics/practices have reduced the scope or frequency of laboratory testing for stable adult patients (i.e. CD4 helper cell count in normal reference range and VL suppression for >2 years on cART) who are highly adherent to treatment and at low risk of adverse syndemic issues. At one Ontario clinic, for example, routine follow-up laboratory work for stable patients consists of tests or analyses for CBC, random glucose, ALT, HIV VL and eGFR. At least one Ontario clinic has developed medical directives designed to curtail unnecessary laboratory testing without compromising patient care (consistent with the Choosing Wisely100 initiative – a campaign to help clinicians and patients engage in conversations about unnecessary tests and treatments and make smart and effective choices to ensure high-quality care). Clinics that have these directives or protocols are encouraged to share their testing experience with other practices. Pilot programs to reduce frequency of testing may inform recommendations in future revised guidelines.14, 101–103 Reduction of CD4 testing for INR may not be advisable.

Comprehensive or combination measures of comorbidity assessment and risk prediction may help to interpret otherwise disparate laboratory results for persons with HIV.

– The Veteran Aging Cohort Study (VACS) Index can be used to predict all cause and specific mortality, neurocognitive impairment and other functional indicators.

– Short term disease progression may be predicted using the EuroSIDA risk-score.

– Cardiovascular risks can be predicted using the ASCVD or Framingham Risk calculator.

– The Canadian Diabetes Association provides a risk calculator for diabetes assessment.

3.6 Because people with HIV are at risk of developing other co-morbidities, providers should consider using comprehensive or combination measures (e.g. VACS Index, EuroSIDA risk score, ASCVD) to monitor for early signs of risk of co-morbidity and/or mortality.104–107

People with HIV are at risk of developing other comorbidities. To provide effective preventive care, providers should use a range of measures to monitor patients for early signs of comorbidity.

3.7 Screening for co-infections and STIs, including hepatitis should be repeated at regular intervals as needed. Most patients should be screened annually for syphilis; patients at high risk (e.g. some men who have sex with men, sex workers) should be screened every 3 to 6 months. Sexually active men and women with multiple partners should be screened annually for chlamydia/gonorrhea.108

For the convenience of both patients and providers, many clinics integrate screening for co-infections and STIs with regularly scheduled VL testing.

3.8 Bone health testing should be conducted in accordance with current OREP guidelines.

To evaluate and manage low bone mineral density, osteoporosis and fracture risk in people with HIV, providers may follow the same principles as for the general population – although some expert practitioners recommend that formal assessment of bone health should commence at an earlier age for people with HIV (i.e. 40 vs 50). In some Ontario clinics, bone health testing is a lower priority than screening for other comorbidities if fractures are infrequent.109 Recent guidelines to assess bone health and risks of fracture or frailty prepared by the Osteo Renal Exchange program (OREP) provide evidence-based consensus on suitable tests for men and women of different ages.110

3.9 Neurocognitive assessments may be appropriate within 6 months of a confirmed HIV diagnosis.111

Asymptomatic and mild neurocognitive impairment without evidence of dementia is known to affect medication adherence and daily and social function. Neurocognitive assessment may be useful in differentiating impairments from depression. It may also establish baseline values and make patients more aware of the impact of HIV on their cognition. Ontario currently has limited capacity to perform these assessments, and their value may be limited since there is no recommended biomedical/ pharmacological therapy for mild neurocognitive impairments other than cART.112 However, there is evidence that both physical exercise and brain fitness exercises may help mitigate or manage mild neurocognitive losses.

LONG TERM HEALTH PROMOTION AND TREATMENT OF OTHER HEALTH ISSUES

3.10 Patients should be offered vaccinations consistent with the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Canadian Immunization guides and recommended immunization schedules for immunocompromised patients (e.g. Infectious Diseases Society of America).14, 113, 114

Some providers may not be knowledgeable about the vaccination needs of people with HIV115 and Ontario’s publicly funded immunization programs may not cover all vaccines recommended for people who have HIV.116 See vaccination schedules and information sheets and checklists prepared by experienced Ontario HIV physicians. Although there are few data on the optimal timing of vaccinations, many practitioners favour providing Hepatitis A and B, pneumococcal and zoster or HPV vaccines when patients are virally suppressed. The decision to vaccinate older adults for herpes and varicella zoster may depend on the patient’s CD4 count.113

TABLE 1: Immunization Recommendations for HIV+ Adults: Canada 2017, Who and When to Treat

| Vaccine | Indications / Recommendations | CD4 restrict | Warnings or Contraindications Specific to the HIV-infected Population | |

| Hepatitis A (HAV) | Recommended for all MSM, IDU, travellers to endemic countries, persons with chronic liver disease, coinfected with HBV or HCV who are non-immune to HAV. 1 dose followed by 1 booster dose at 6 months (see specific product monograph); check HAV IgG one month post immunization and if negative revaccinate | |||

| Hepatitis B (HBV) | Administer to all patients without evidence of past or present hepatitis B infection; double dose recommended; if weak response (<10 IU/L) at one month repeat vaccine series; HBV vaccination should also be offered to those who have positive hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) with negative HBsAg and anti-HBs results and undetectable HBV DNA; One monovalent vaccine has higher levels of HBV antigen and is preferred to HAV/HBV combined vaccines. Consider repeating anti-HBs yearly if responded to initial immunization and if <10 IU/L offer booster dose. See product monographs regarding booster doses. | |||

| Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) | No longer recommended except for patients with asplenia or hyposplenism, complement deficiencies, lymphoreticular or hematopoietic malignancies, bone marrow transplantation, alcoholism, or cochlear implants. | Defer in the presence of any acute illness to avoid superimposing adverse effects from the vaccine on the underlying illness. | ||

| Human papillomavirus (HPV) | HPV vaccine 4 or 9 is recommended for the prevention of genital warts, anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) and vulvar, vaginal, cervical and anal cancer in females age 9 and older and males between 9 and 26 years of age, including males who have sex with males. HPV vaccine 4 or 9 may be administered to males over 26 years of age. HPV vaccine 4 or 9 is given as one dose followed by one booster dose at 2 months and a second booster at 6 months. | HPV vaccines can be administered to immunocompromised patients however the immunogenicity and efficacy have not been fully determined in this population. A 3 dose schedule is recommended. | ||

| Influenza (inactivated injectable or live intranasal vaccine) | 1 dose annually preferably during autumn. Should be offered during pregnancy. Vaccinate international travellers yearlong. | Live intra-nasal vaccine contraindicated in patients receiving immunosuppresive therapy or who are in an immunosuppressed state | ||

| Measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) | If not immune to MMR and CD4 count ≥ 200 cells/μl. 1 dose and 1 booster dose can be considered in HIV+ individuals who are not immunosuppressed. | ≥ 200 cells/μl | Contraindicated in patients receiving immunosuppresive therapy or who are in an immunosuppressed state, or individuals with active untreated tuberculosis, or active febrile illness, or pregnancy. | |

| Meningococcal ACYW-135 | Recommend conjugate vaccine (Men ACWY-135 ), 2 dose primary series separated by >2 months; repeat every 5 years. | Not indicated for the treatment of meningococcal infections. | ||

| Meningococcal B | Consider MenB vaccine to cover serogroup B. | Not indicated for the treatment of meningococcal infections. | ||

| Pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate (PCV13 or Pneu-C-13) | Recommended for all adults with CD4 ≥ 200 cells/μl. If the patient is naive to Prevnar and Pneumovax, administer Prevnar first; then administer Pneumovax ≥8 weeks after Prevnar, then administer Pneumovax ≥5 yrs after last Pneumovax. If the patient has already received 1 dose of Pneumovax, administer Prevnar ≥1 yr after last Pneumovax, then administer Pneumovax ≥5 yrs after last Pneumovax. If the patient has already received 2 doses of Pneumovax, wait ≥1 yr after last Pneumovax and then administer Prevnar. When ≥65 yrs and ≥5 yrs after last Pneumovax, administer Pneumovax. 3 maximum lifetime doses of Pneumovax. | ≥ 200 cells/μl | Can be administered at any CD4 count, however best immunogenicity at ≥ 200 cells/μl. | |

| Pneumococcal polysaccharide (PPSV23 or Pneu-P-23) | ≥ 200 cells/μl | Recommended ≥ 200 cells/μl. | ||

| Tetanus, diptheria (Td) | Td booster every 10 years. If Tdap or Tdap-IPV has not been previously administered, a one-time Tdap or Tdap-IPV booster should be used in place of Td booster, regardless of interval between prior Tdap or Td immunization. | |||

| Tetanus, diptheria, pertussis (Tdap) | One lifetime dose for pertussis component. If not previously administered, regardless of interval between prior Tdap or Td immunization patient should receive one dose of Tdap. Administer with each pregnancy at weeks 27-36; can be given regardless of interval between prior Tdap or Td immunization. Consider for HIV positive adults caring for infants <12 months of age at work or home. | |||

| Tetanus, diptheria, pertussis, polio (Tdap-IPV) | Consider if vaccination for polio is required. For general indications, refer to Tdap. | |||

| Varicella – live | Administer to HIV-infected persons with a CD4 count ≥ 200 cells/μl who do not have evidence of immunity to varicella. 1 dose followed by 1 booster dose (see specific product monograph). | ≥ 200 cells/μl | Contraindicated in patients receiving immunosuppresive therapy or who are in an immunosuppressed state, or individuals with active untreated tuberculosis, or active febrile illness, or pregnancy. Avoid salicyate therapy for 6 weeks after varicella immunization. | |

| Zoster – live | Approved in patients > 50 years, recommended to all patients > 60 years with CD4 ≥ 200 cells/μl; hold antivirals (acyclovir, famciclovir, valacyclovir for 24 hours before and 14 days after immunization). Prior zoster infection not a contraindication however vaccination should wait until 1 year after last episode. 1 dose. | ≥ 200 cells/μl | Contraindicated in immunosuppression due to AIDS, cellular immune deficiencies, lymphoproliferative disorders, or immunosuppresive therapy. Contraindicated in individuals with active untreated TB. | |

| Enterotoxigenic Escheria coli (ETEC)/cholera | Consider if travelling to endemic areas. 2 oral doses at least 1 week apart. 1st dose at least 2 weeks before departure, 2nd dose at 1 week after 1st dose. If patient received the last dose more than 5 years before, a complete primary immunization (2 doses) is recommended. May provide booster dose after 2 years if continued risk | |||

| European tick-borne encephalitis | Consider if travelling to endemic areas for several weeks with frequent and prolonged outdoor activities. * not available in Canada as of Feb 2014 * | inactivated vaccine | ||

| Japanese encephalitis | Consider if travelling to endemic areas. The primary vaccination series consists of 2 separate doses separated by 28 days given >1 month before exposure. A booster dose (third dose) should be given within the second year. | |||

| Poliomyelitis |

|

|||

| Rabies (pre-exposure) | Pre-exposure rabies immunization should be offered to people at risk of contact with rabid animals (laboratory workers, veternarians, animal control and wildlife workers, spelunkers, and hunters). | |||

| Tuberculosis (TB) | Do not use BCG live vaccine in HIV-infected persons. | BCG vaccine contraindicated. | ||

| Typhoid | Consider if travelling to endemic areas. 1 dose >2 weeks before exposure, consider booster dose every 2 years for individuals at risk. | ≥ 200 cells/μl (live vaccine) | Avoid live, oral vaccine in immunosuppressed patients with CD4 < 200 cells/μl. | |

| Yellow fever | Consider if travelling to endemic areas. If immunocompromised 1 dose every 10 years if continued risk, otherwise 1 dose for life. | ≥ 200 cells/μl | Live vaccine. Contraindicated in immunosuppressed patients with CD4 < 200 cells/μl. |

3.11 Patients should be encouraged to adopt healthy living practices14 and take targeted effective supplements, including:Author: Anita Rachlis. Reviewed by Fred Crouzat, Jean-Guy Baril, Dominique Tessier, Phil Sestak, John Gill and Curtis Cooper.

- Weight bearing and cardiovascular exercise

- Weight control

- Reducing/stopping smoking

- Limiting alcohol intake

- When indicated, supplementation with Vitamin D and calcium.117

The U.S. National Institutes of Health and others recognize the importance of people with HIV maximizing their health and maintaining functional wellness, which is defined as “a person-centered balance between internal (individual responses to stress, illness, medication; personal or cultural behaviors) and external factors (learning new or adaptive strategies for current roles, managing one’s physical, emotional and environmental health) affecting health, and developing action plans toward healthy living and wellness.”

Exercise is known to improve strength, endurance and body composition in people with HIV and may improve cognitive functioning.118–120

Smoking cessation should be a high priority for patients once their HIV infection is stable. Smoking significantly reduces life expectancy for people with HIV.14, 15, 121 Providers focused on managing HIV may neglect the risk of smoking: in one study less than half of HIV patients discussed smoking or cardiovascular risks with their providers – despite the impact these health risks have on their long-term well-being.122Recent reviews provide comprehensive strategies for physicians and clinics to actively support smoking cessation in people with HIV.121, 123–125 In Ontario, the Positive Quitting partnership has assembled smoking cessation intervention resources specifically for use in HIV clinics.

The American Dietetic Association has developed comprehensive recommendations for nutrition assessment and interventions for persons with HIV.126

3.12 Social service assessments and referrals — especially those related to housing, food security, income support, access to medicine and peer or family support — should be coordinated with medical evaluations and other services, such as mental health care.32 People with HIV receiving case management in community-based mental health services would benefit from integrated care delivered at the community program site that jointly addresses their co-occurring psychiatric, addiction and physical health needs as well as, perhaps, some medical care.127

Studies show that men with HIV receiving case management in community mental health settings have greater unmet needs for food, money, psychological distress and safety needs than men in those care settings who do not have HIV. These results likely apply to all people with HIV in these settings.

Additional Population-Specific Considerations

WOMEN

3.13 HIV care teams should establish an appropriate schedule of follow-up testing for women, including pap tests and mammography for women >50, based on current recommendations.14, 17

3.14 Hormone replacement therapy is not recommended for women born female except for limited purposes.14,17

3.15 Women should be asked about sexual function/dysfunction.71

3.16 Women of child-bearing age should be asked about their plans and desires regarding pregnancy consistent with Canadian Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada and Canadian HIV pregnancy planning guidelines.14, 17, 128, 129

Pregnancy planning involves partnership considerations and guideline driven activities for both women and men and varies depending on discordant or concordant HIV status.

3.17 Pregnant women with HIV should be treated for their infection and given appropriate pre-natal care and counseling.14, 17, 128

Pregnant women living with HIV should be made aware that consistent use of cART and avoidance of breastfeeding can reduce the risk of perinatal transmission to < 1%.129

3.18 Annual digital rectal exams are recommended for all HIV+ men who have sex with men, and consideration should be given to anal pap tests or other screening such as PHV DNA testing and high resolution anoscopy.

There is not enough evidence at this time to fully recommend anal pap tests or other screening such as HPV DNA testing and high resolution anoscopy for all HIV+ men who have sex with men.130 However, if these services are available (access is limited at the current time in Ontario), they may be ordered based on clinical judgement.

3.19 Men should be asked about sexual function/dysfunction. Men with decreased libido or erectile dysfunction should be tested for serum testosterone levels.17

4. Antiretroviral Therapy Across the Continuum of Care

General Recommendations

These guidelines recommend, based on strong evidence, that patients be offered cART as soon as possible after being diagnosed with HIV. People who are newly diagnosed and ready to access treatment immediately should be supported to do so. However, for many people, diagnosis is an emotional shock and they may find it difficult to make an informed decision to initiate cART quickly. It may also take time to address any factors that may affect a patient’s ability to maintain a cART regimen (e.g. willingness, pharmaceutical access, syndemic factors).

Until there is a cure for HIV, antiretroviral therapy is a lifetime commitment, so patients may need support to manage and adhere to therapy throughout the life course.

Although evidence explains when to start therapy, guidelines can help providers and patients implement cART effectively. Optimal care and services delivery can contribute to adherence. Good provider-patient relationships measured across relevant domains (general communication skill and empathy, overall patient satisfaction, willingness to recommend the physician, physician trust, HIV specific communication regarding cART in the context of daily life experiences and skilled adherence dialogue) improve adherence.33, 50, 131 See Appendix C for a the relevant domains and advice on how to means to survey patients. The US DHHS has developed a tool (Table 13) to help providers improve adherence, which identifies barriers to adherence and provides an adherence issues framework. Note: Patients may not always give candid answers in face-to-face surveys. Clinics/practices may consider ACASI (Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview Software) or electronic tablet surveys. (See Section 5.0, Promising Practices.)

Effective adherence support techniques – such as phone or electronic reminders and active follow-up contacts, a strong patient-provider relationship that leads to greater understanding of the patient’s circumstances and beliefs, the use of expert conversation skills and reinvigoration of previously delivered messages – can also used be used to retain patients in care (see Section 5.0). Clinics/practices may find it useful to combine retention and adherence efforts. Note: Some strategies, such as reminder systems, may not be effective for patients with complex needs who, for example, may not have phones or access to the Internet. Technology-based or conventional reminders to take medications may be less effective without solid relationships and patient feedback.

INITIATION AND LIFETIME COMMITMENT

4.1 Providers should obtain relevant laboratory values — such as CD4 T-cell count, VL, CD8 count, viral genotyping, hypersensitivity (HLA-B*57:01), applicable tropism tests and other laboratory values necessary for prescribing — when treatment is initiated.13, 14, 20

4.2 Patients should be fully involved in decisions to select appropriate regimens and initiate cART. Providers must be prepared to: discuss the issues thoroughly in easy-to-understand language; explore the patient’s understanding and beliefs related to the potential benefits and risks of initiating treatment; and assess the patient’s readiness for, acceptance of and commitment to antiretroviral therapy.

Successful long term adherence is affected by many factors; however, patients’ beliefs about the importance of therapy and their sense of self-efficacy may be critical.51, 132–134

4.3 Providers should develop the skill/ability (through mentoring, training or the use of tested interviewing techniques) to communicate effectively about cART and discuss adherence.64, 131

In collaboration with experts in physician/patient communication, European guidelines have developed tested interviewing techniques to explore a patient’s readiness to start and adhere to cART (see Appendix C and “Ready4Therapy” 135). Some patients may benefit from motivational interviewing techniques. Key messages to communicate to patients include: the fact that some adverse effects they may experience when first taking cART are temporary; and regimens can be changed if side effects continue.

Providers may make it easier for patients to discuss non-adherence if they explain the reason for the discussion, do not apportion blame, and probe the patient’s preferred types of support.48

4.4 Providers and patients should discuss any barriers to accessing or adhering to therapy when patients start cART and at regular intervals thereafter.

Barriers may include lack of insurance or drug coverage, other medications and supplements the person may be taking, and any mental health or substance use issues that could affect the ability to take cART consistently.14

Supportive partners or patient caregivers may be included in discussions about possible barriers.136 If drug cost is a potential barrier, clinics/practices can ask the government-run Trillium Drug Plan to fast-track the processing of the patient’s application.

4.5 In light of new evidence on the benefits of early treatment, providers should review the findings with any patients who have hesitated to initiate cART and discuss their concerns.137

ADHERENCE TO cART OVER THE LONG TERM

Adherence to cART is essential for patients to achieve and maintain VL suppression, recover CD4 T-cells, avoid drug resistance, improve overall health and survival, and decrease the chance of onward HIV transmission. However, adherence may wane over time and be influenced by age, personal and social factors, number of years since diagnosis, previous therapy, access, substance use and mental state.132, 138 Provider skill and involvement are crucial to retain patients in care and help them achieve high levels of medication adherence.13 Providers should consider nuanced approaches.

4.6 Clinicians should consider and support cART regimens with lower pill burden.13, 20

Regimens that have lower pill burdens (e.g. once daily or, at most, twice daily dosing) improve adherence. The development of new single tablet daily regimens may improve adherence; however, their effectiveness will depend on their tolerability for patients and their efficacy in suppressing VL over the long term.139–141

As generic equivalents of compounds now used in single tablet regimens become available, publicly funded drug programs may pressure providers to prescribe the individual components separately – thereby increasing pill burden and possibly having a negative effect on adherence. If the pill burden of generics is significant, providers may need to advocate for non-generic prescriptions for their patients. The prospect of long-acting injectable formulations of cART, now in the research and development phase, may help overcome issues of pill burden but they will create significant new implementation challenges for patients and the health care system.142, 143

4.7 Clinics/practices should implement strategies that support/sustain adherence, including managing drug interactions between cART and other medications and/or substances the patient uses,13, 16, 48and making effective use of nurses, social workers and community-based counsellors.

A number of strategies, either singly or in combination, have been shown to support adherence (see table) – although most studies were conducted in small populations or unique settings and may not be broadly applicable throughout Ontario.144, 145 For example, the use of clinical pharmacists in ambulatory care or in-patient medical centers improves adherence; however, data about the benefits of using community pharmacists is lacking.146 Working with pharmacists may improve prescribing practice by focusing attention on interactions between cART and other medications and with a variety of drug classes including illicit substances.13, 147, 148 When feasible, patients may also use medication apps, such as Liverpool HIV iChart149to understand drug interactions.

Nursing staff, social workers and community based counsellors are key providers in improving adherence.

See a sample validated screen questionnaire to conduct motivational and behavioural interviewing.150

| Strategy | Evidence from Guidelines or Articles | Notes |

| Education and counseling | IAPAC IAWHO: “essential” | Interventions delivered to individuals over 12 weeks or more and/or targeting practical medical management were successful as evaluated by systematic review. Effectiveness increased when the intervention was combined with weekly text messages and peer support. |

| Individual one-on-one counseling | IAPAC IIACDC, HRSA recommended | Using one or more counselling techniques |

| Group education/counseling | IAPAC IIC | |

| Multidisciplinary education and counseling | IAPAC IIIB | |

| Provided by nurse or community based counselor | IAPAC IIBSystematic review | Nurse-led counselling significantly improved adherence |

| Smart Phone reminders or SMS/landline or verbal telephone | IAPAC IBWHO Guidelines: strong recommendation/moderate support.

A recent systematic review found support for the efficacy of text messaging. Several rapid or systematic reviews find low or mixed evidence for smart/cell phone/landline-verbal reminders or texts. |

One systematic review found good positive support for weekly rather than daily text messaging to improve daily adherence. User fatigue may be an issue with sustainability of the strategy. Efficacy of text messaging may be increased if the messages are bi-directional, include personalized messages and are matched to dosing schedules. Messages that convey “self-care” questions rather than frank reminders may be beneficial. Marketed medication “apps” have not been sufficiently tested and may require quality review before use.WHO finds little evidence to support other reminders such as alarms, phone calls or electronic diaries. According to pilot phase studies, youth may benefit from use of texting technology. |

| Use of HIV specialist clinical pharmacists | One systematic review found significant improvement in adherence. A retrospective review found significantly higher likelihood of durable VL suppression in treatment naïve patients referred to pharmacist assistance management. | Applicable to ambulatory or in-patient care in a multidisciplinary setting; community pharmacist data lacking. |

| Monitoring by self report(with checks of pharmacy refill data) | IAPAC AIIIAPAC CC BII | Important for collecting data on adherence |

| Peer support/community health workers (CHW) | IAPAC IIICSystematic review | The effectiveness of peer/CHW support increased with the duration of intervention, focus on medical management, use of directly observed therapy and focus on targeted populations (e.g. substance users). |

| Motivational interviewing | Evidence from systematic reviews is mixed. | Resource and time intensive; may be more suitable for persons who use substances or alcohol or who experience syndemic health and social issues. |

| Case management | IAPAC IIIB | For use with people who are homeless or marginally housed |

| Directly observed therapy | IAPAC CC BI | Only in limited situations such as incarceration; otherwise not recommended; not shown to be effective for substance users unless combined with significant enhanced medical and social support. |

| Electronic drug monitors or biological sampling | IAPAC IIC | Not routinely recommended. |

| Pill boxes | IAPAC IIIB, IAPAC CC IIB | Routinely used in health care; especially helpful for people who are homeless or marginally housed. |

| Telephone based cognitive behavioural therapy | Pilot RCT | May improve adherence in populations with depression. |

| Community-based advanced practice nurse intervention with weekly visits and coordinated HIV and mental health care | Longitudinal RCT | For persons with serious mental illness. |

| An adherence testing and training period in which a placebo is administered | Consider for use as part of educational efforts for adolescents or youth initiating treatment. |

Additional Population-Specific Considerations

Adherence can be particularly challenging for certain populations.

WOMEN

4.8 Clinicians should provide additional adherence support for women during the postpartum period.

During the postpartum period, women with HIV may experience problems with adherence and their VL may rebound. They should receive support with adherence as well as comprehensive case management services before being discharged from hospital and for a period of time after. Women who engage in care within 90 days of delivery are significantly more likely to be retained and to maintain a suppressed VL.19, 21, 151–153

4.9 Clinicians should be aware of emotional and mental health issues that may affect cART adherence in women.

Women may experience strong emotional reactions to physical changes associated with cART, such as fat distribution or changes in adipose tissue. They may also be more likely to experience mental health conditions that affect adherence (e.g. depression, anxiety). These conditions may be linked to previous or ongoing trauma, partner violence or abuse.154

PWID AND RELATED SUBSTANCE USE

4.10 Individuals who use substances or who have heavy alcohol use may benefit from particular adherence supports, including medication to address opioid dependence and education about cART interactions with substances. Patients should also be encouraged to reduce substance and alcohol use.17, 61

Substance use may impair a patient’s ability to adhere to daily regimens. In some cases, patients may intentionally skip medications when drinking or using substances because of mistaken beliefs about interactive toxicity.155, 156 The World Health Organization’s AUDIT screen may be used to identify high alcohol use.157

5. Retention and Ongoing Care

General Recommendations

RETENTION, RELINKING AND RETURN TO CARE

For people with HIV to achieve optimal health outcomes, they must receive ongoing care over their lifetime. Missed clinic visits and other gaps in care are associated with increased mortality, reduced cART adherence, increased hospitalization and lapses in ability to manage comorbidities.158, 159 Patients, especially those with complex needs, may experience interruptions in care.160

A number of indicators have been proposed to measure patient retention in care, including clinic encounters/visits, timing of VL or CD4 tests, and test results during a calendar year.161, 162 Most recently in Ontario, care engagement in any year was defined as:

- “in care” – at least 1 viral load or CD4 cell count

- “continuous care” – at least 2 viral loads or CD4 cell counts at least 90 days apart.

- “being on ART” – based on prescription medication recorded in medical charts.163

However, laboratory tests and pharmacy records may not provide a complete picture of retention and engagement in care for clinical purposes164 or document co-/multi-morbidity care provided at different locations.

Although there is evidence to support some clinic and provider-initiated retention strategies, there is often not enough data to assess their impact on biological outcomes. Data are also lacking on effective techniques to: re-engage people in care after they have been lost to follow-up; follow patients over many years; or address the needs of specific populations.165–167 The following recommendations include both evidence-based interventions and “promising practices” to enhance retention.

5.1 Clinics/practices should actively and systematically monitor their patients’ retention in care. They may use a combination of actual clinic visits, patient laboratory reports, pharmacy requests and other data in medical records to create a comprehensive retention picture. Systematic monitoring may require multiple ways to track individual data.13, 20